Meditation / Sitting - Postures, etc.

See also this page:

https://www.meaningofwilderness.com/meditation-overview/

I will be adding more information to this page as time permits.

June 8, 2020. For the past two years or so I have been sitting solely in a chair, with my shoulders slightly slouched forward. This helps me relax my abdomen which is been in a knot since sperm met egg. I find that if I lean back, or lay down, it’s more difficult to relax my abdomen. Find out what’s best for you.

I will first discuss sitting postures. While I no longer consider myself a Zen Buddhist -- I am not a anything -- I do find the Zen method of physically sitting helpful. First off, I don't want anyone to think they have to sit in some convoluted cross-legged posture to meditate (I prefer the word sitting since it implies less willful intention). I did sit half lotus for 25 years -- it took me a full year to limber up my legs before I was able to do it -- but now I sit most of the time on a simple bench, or often in a chair because this helps me relax my abdomen and shoulders. For myself, stability and comfort are the main criteria. I prefer to sit for a full hour at one time (I may adjust my position during that time) and sitting cross-legged that long causes me serious knee problems. Note I also realized recently I was getting varicose and spider veins, likely due to long hours of sitting, both meditation and at the piano as well as at the computer. I’ve since read that flexing your ankles perhaps every half-hour can help prevent this. So I try to sit in a posture so I can do this at the halfway point — by having my ankles hang off the mat.

I’m reasonably certain my quarter-century of half lotus sitting damaged the meniscus of both knees, especially the left which was usually the one raised higher. This caused knee problems that I solved after starting the strength training exercises listed at Exercise: A Spiritual Necessity.

For myself, stability and comfort are the main criteria.

This website has photographs of the various postures and some basic helpful information for the beginner. But I make no attempt keep my back straight: it’s much more important for me to relax my abdomen.

Frankly, I don't take many of the instructions on meditating at that site too seriously. One of the things I could never stand at the Zen Center was how the guards, I mean monitors, would make rounds every 10 minutes flailing away with the kyosaku (a flat bladed stick used to strike the soft tissue on top of the shoulder) and adjusting everyone's posture. Mine was always "off" due to my tension. I think it's far better to be relaxed than to be forced to fit some preconceived idea of the "best." Also, the sitting bench shown has what I believe is too steep of an angle downward. If you purchase a bench (just do a Google search on meditation bench; you'll also find information online about meditation cushions if you wish) with that much of an angle you might want to try gluing a piece of carpet foam (or two) across the front half to make it less steep. You can put either a rectangular meditation cushion, or a pillow of any kind on top of the bench, or do as I do: cut up

carpet foam (look for the softest possible) into 12 x 18 inch pieces -- I use about 4 -- put them on top of each other inside a pillow case, and tie the pillowcase down to the top of the bench. This allows me to get precisely the height I want. I also like to sit on a mat (do a Google search on meditation supplies); these are about 32 inches square. Because it's gotten quite hard over the years I put a couple layers of carpet foam on top (lately I have found foam too hard for a very sensitive spot on my left ankle, so I’ve put soft 2-inch foam on top of it). You could make your own with a few layers of foam covered by a pillowcase. I place my bench at the edge of the mat and this way my toes hang off the edge of the mat, which is more comfortable. The foam (try Home Depot or Lowe's; they'll sell you a small amount) could be cut narrow so it fit between the legs of the bench, and wider in front where it goes under the knees. Sometimes just to stretch I spread my knees apart sideways some. I have also made small platform for the foam made of plywood on top of two by sixes — so my toes can hang freely.

As the site says, you can get by quite well for some time just using folded up blankets and bed pillows, etc. If you are kneeling, fold the blankets in a narrow fashion so they will fit between your legs, and then put a pillow on top. That's what I used at first, but now I find the stability of a bench important.

In Zen, generally, you try to have three-point stability: the buttocks and your two knees. To do this you need to raise the buttocks up, on a cushion or bench, higher than the knees to a height that is just right for you. If you purchase a formal round meditation cushion you may find you want some other material underneath it to make it precisely the right height. If you lean forward somewhat after you get in position, this will thrust your buttocks out behind you and make it possible for the upper body to remain in a relaxed and upright position. (I try to sit with my upper body roughly the same way playing the piano.) The knees should rest solidly on the floor, or mat. Frequently one sees photos of someone sitting cross-legged either without a cushion, or with the knees pointed up in the air. This person is not meditating; they're faking it. It's impossible to hold that posture comfortably for very long.

If you're sitting in a chair, you should sit on a cushion that allows a slight forward down-slant. My wife and I both purchased expensive three-way adjustable executive chairs for sitting when we started having knee problems 10 years or so ago. They're useful because you can adjust the height, and also the tilt of the chair. Because they didn't tilt forward enough -- the most forward position was horizontal -- I removed the bolts holding the chair to its post, inserted a one-inch piece of wood to raise up the back, and then screwed in longer bolts. This allowed a slight forward down-slant. . Anne sits that way all the time. She puts an inflatable backpacking mattress (Thermarest) on top of the chair to make it more comfortable. Unfortunately, I’ve discovered after regular use recently that these chairs make tiny noises. I figured out a very complex way to eliminate them but I don’t recommend them for anyone else for that reason. Use an ordinary chair and foam to make it the right angle or comfort, etc.

As far as the hands go, I just rest one on top of the other in my lap (left one on top) -- I use one pillow on top of another to support them. (But go ahead and try the cosmic mudra shown at the website above if you want. Philip Kapleau claimed it was superior -- maybe it is.) And when my shoulders start getting tense I break the "rules" and rest my hands on the sides of the bench to stretch my neck muscles.

Also, as mentioned in Cabeza, I prefer to keep my eyes closed, while Anne keeps hers open and directed downward, unfocused -- which is what you are "supposed to do." As far as methods of meditation go, you're welcome to try any of those discussed at the above-listed site, but as I mentioned in Cabeza, I jettisoned all of them long ago. The main reason is that they all involve to one degree or another using the will. See the chapter "The Unfree Will" in Cabeza.

What I wonder about, and do not know the answer to (at least for others; as I wrote in Cabeza, everyone has to figure out for themselves what meditation/sitting is all about), is whether these practices, or the far more elaborate ones of other traditions, really just serve as a way to prevent the profound fear of death of the individual separate self from coming to the surface. I think it’s likely to have one’s cake and eat it too. I.e., maybe have some little spiritual experiences but still hold onto the individual self.I also wonder if keeping the eyes partly open (instead of closing them, as I do) does the same. For myself and Anne, the only thing that "works" or at least has a chance of "working" is to just see if it's possible to allow the mind to be with itself, without trying to do anything. I suggest that anyone serious about meditation reread Cabeza and mark all the relevant parts for future reference. (As I wrote in the book, I myself find it helpful to reread it. I should remember that, I say to myself.) If at that point anyone has further questions or observations they're welcome to e-mail me. I will be happy to converse with anyone seriously interested.

Finally, here is an epilogue to chapter Guru III

Epilogue: In January 2011, after looking at the Springwater Center’s website I decided to attend

a few days of the Quiet Weeks (a relatively recent innovation) period in February, and also to rejoin the Center. I have since attended two more three-day self-directed retreats and have found these

times quite helpful, to say the least. I suggest that anyone open to Cabeza’s message and interested in either a structured or self-directed retreat, on a uniquely beautiful property in upstate New

York, may wish to do the same. See www.springwatercenter.org and www.meaningofwilderness.com for more information. Independent of what has been written in this chapter is that the great legacy of

Toni Packer, who is now permanently bedridden in her home not far from Springwater, is to have created a place where people can come and find out for themselves if it’s possible to simply be with

their own mind. On their own terms. However it works best for them. Without nonsense. Without extras. Without . . . whatever. This is something very precious. I hope it will endure, at least as long

as things human are capable of enduring. —Phil Grant, March 2011

Added February 9, 2013:

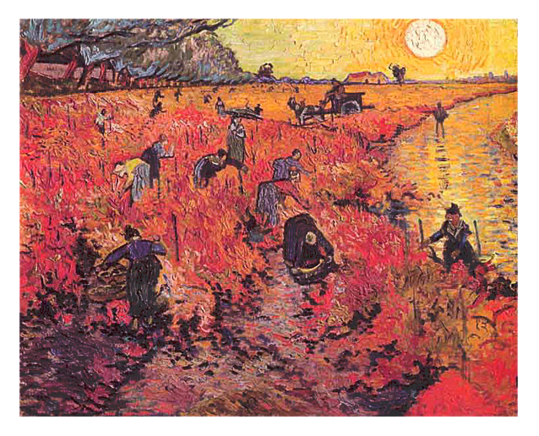

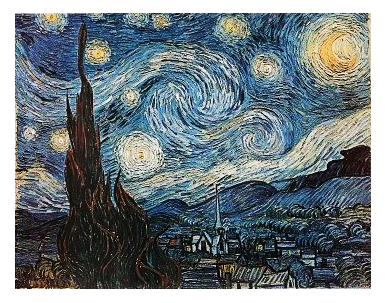

Below are pictures of Vincent van Gogh from a card I have given to a number of people at the Springwater Center, and following that is a letter regarding other ways to look at the spiritual endeavor

that was included.

Type the document title]

“But when shall I ever get around to doing the starry sky, the picture that is always in my mind?

. . . . . .

Yet you have to make a start, no matter how incompetent you feel in the face of inexpressible perfection, of the overwhelming beauty of nature.” —Vincent van Gogh, June 18, 1888, to fellow artist

Emile Bernard

Vincent van Gogh, writing to his brother Theo, November 3, 1888: “But if only you’d been with us on Sunday! We saw a red vineyard, completely red like red wine. In the distance it became yellow, and then a green sky with a sun, fields violet and sparkling yellow here and there after the rain in which the setting sun was reflected.”

On December 24 of that year came the famous incident when he cut off part of his ear, after which he was hospitalized.

Then in March he wrote to Theo: “How strange these last three months do seem to me. Sometimes moods of indescribable mental anguish, sometimes moments when the veil of time . . . seemed to be torn apart for an instant.” And: “To suffer without complaining is the one lesson that has to be learned in this life.”

Dear person at the Springwater Center,

Over the last several months I have given this print of The Red Vineyard, along with these quotes of Vincent van Gogh, to several people at Springwater. Since all appreciated the print, and some also expressed how profoundly relevant Van Gogh’s words were to their own spiritual endeavor, I’ve decided to give them to others at the Center—call it a late (or early) season’s greetings card—and also include what I think of as its sister composition, Starry Night, along with a brief commentary about what these words, and paintings, mean to me.

First, I consider The Red Vineyard a perfect visual expression of the words found in The Zen Teaching of Huang Po: “This One Pure Mind, the Source of everything, shines forever and on all with the brilliance of its own perfection.” And perhaps both paintings hint at Huang Po's “That which is before you is it, in all its fullness, utterly complete. There is naught beside.”

“Sometimes moods of indescribable mental anguish, sometimes moments when the veil of time . . . seemed to be torn apart for an instant.” Huang Po: “Beginningless time and the present moment are the same. . . .” Albert Einstein, whose theory of relativity proved this: “The difference between past, present, and future is only the matter of an illusion. . . .”

“To suffer without complaining [even just to oneself or the universe] is the one lesson that has to be learned in this life.” If there is an external cause of our suffering it may be appropriate to avoid it in one way or another, if possible. If not, or as is often the case the cause is internal, then the “lesson” involves allowing ourselves to feel that suffering without reacting, without “complaining.” For this person at least, this is what sitting meditation is all about, what a life of genuine spirituality is all about: Just allowing the mind to be with itself with no method or technique that might be used as a defense; without even trying to be attentive, which can be another defense. Seeing if it’s possible for there to be a letting go of countless layers of tension—and if not, to just be with the tension—and other inner defenses and allow deeply buried feelings, at times possibly intense anxiety or even “indescribable mental anguish,” to come up into full consciousness without acting on or reacting to them. Just letting the seemingly devastating truth of the individual self’s utter insignificance—a truth conveyed, I feel, by Starry Night (imagine looking up into an entire sky like that) —begin to arise into awareness. To let all this happen, on its own, without interference or distraction, this is truly to suffer without complaining. And it may be then that it is possible for “the veil of time . . . to be torn apart . . . .” For genuine inner freedom, joy, and a profound understanding of the human condition to be known. . . . And for mind . . . to know Mind; Being . . . to permeate being.

In the early years of the Center Toni would sometimes speak of a time during a retreat at the Zen Center when she was experiencing intense back pain. Somehow she was able to let go of all resistance and just be there with the pain. She suffered without complaining. And though she didn’t say so outright, I strongly suspect she had, then, a moment when the veil of time was torn apart. And I also strongly suspect this moment is what led to her being named a teacher by Philip Kapleau . . . and in turn to her leaving the Zen Center and founding the Springwater Center.

So without one person, close to 40 years ago, seeing she had no choice but to suffer without complaining . . . Springwater would not exist. And you would not be reading this note.

“Has to be learned.” Sadly, Van Gogh could not live his own lesson to the end. He killed himself. But perhaps his words, and his art, can live on through us, as we toil on in our own red vineyards . . . suffused with sparkling light . . . with the “Sun” . . . “the Source of everything” . . . Illuminating all.

Phil Grant

P.S. The above themes, in different words, form the heart of my book, Cabeza and the Meaning of Wilderness: An Exploration of Nature, and Mind, should one wish to pursue them. Anyone who likes these Van Gogh paintings should at least appreciate the 24 pages of photos in Cabeza.

P.P.S. Recently I have been listening to the Miserere (Lord have mercy on me) by Gregorio Allegri. (Search—YouTube Allegri Miserere Tallis Scholars 1600—for what I think is the best performance.)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nKj1iK2WKS8

One comment on Youtube reads: “Miserere Mei Deus (Allegri) is absolutely the most devout and beautiful piece of music the human ear could ever know.” I find it hard to disagree. There is an extraordinary letting go of self—and theTallis Scholars, more so than other groups, are especially attuned to this—that has much to teach us in these 12 minutes of supremely spiritual 17th-century music. The words, from Psalm 51, include, “For You are not pleased with sacrifices, else I would give them to You; neither do You delight in burnt offerings. The sacrifice of God is a contrite heart: a broken and contrite heart, Oh God, You will not despise.” It is clear from the music that Allegri understood this to mean what we would call the offering, the sacrifice of self. This is another way of looking at sitting: as an offering of that infinitely painful and limiting self. There are also the words, “my sin is ever before me.” Saint Teresa of Ávila wrote in The Book of My Life, “My life felt very heavy to me, because prayer illumined all my faults.” Exactly. This is what sitting does. It illumines the separate self, placing it ever before us. Another Christian mystic wrote that in prayer and meditation we enter into what he called “the cloud of unknowing.” But we will not find God there [at least not for a good long while], rather the “foul, putrid lump of self.” This is why sitting goes so against the grain; we don’t want to know about that lump. And why a significant daily commitment to it is so essential. But if we do allow that painfully limiting, straitjacket lump of self to come up into full view, without reaction, suffering without complaining, perhaps these words from the psalm will then apply: “Behold, You delight in truth in the inward being, and You teach me wisdom in the secret heart.” The “You,” is, of course, What we really are. In the words of English mystic Lady Julian of Norwich, “God [by whatever name you want to call IT] is the ground of our being.”

Since we all have so much resistance—the resistance, the fear, that is at the root of “indescribable mental anguish”—to this letting go of self, I will suggest that one could do worse than to listen to this piece periodically as part of one’s daily meditation. And while in general I would say that listening without visual stimulation is the best way to allow the greatest music to penetrate to one's core, one might, one or two times, wish to see the live performance by the Tallis Scholars, performed in a basilica in Rome, at the link below. 12 very ordinary-looking people making, by means of the human voice alone, the most extraordinary music unimaginable. Music offering a glimpse through the “veil of time,” the veil of self.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xpzdB0G3TJU

[The Tallis Scholars performance of the Allegri Miserere is also available at amazon.com on CD or as MP3 download (the other works on the album are much less interesting). To make things confusing they have made a new, 2007 recording in addition to the 1980 recording that the top link goes to. There is a difference of opinion at Amazon as to which is better. I only know the 1980 one (reissued 2001/2005?; there’s a gold crucifix on the cover. Search "tallis scholars allegri"—it’s the top one) and it sounds perfect to me. I suggest going with that one if you buy it from Amazon. Other works of deepest spirituality—by composers who clearly had, at the very least, moments when they saw through the veil of time—are discussed in Cabeza, and also are listed here.]

One other YouTube comment on the Miserere:

“Now ...

I know .....

There is.....

God ....”

Yes.